What, you might ask, have advanced brain machine interfaces got to do with global futures?

Quite a lot as it turns out!

A couple of weeks ago, I participated in a discussion on the the governance and ethics of brain machine interface technologies in a meeting of the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine Committee on Science, Technology and the Law (my comments are at the end of this article). This was a scoping discussion to get a sense of the potential issues here that may need to be addressed moving forward, and was prompted in part by the developments coming out of Elon Musk’s company Neuralink.

Much as Musk has had an outsized impact on electric vehicles, the space industry, and even tunnel boring, he’s setting out to transform the brain machine interface business.

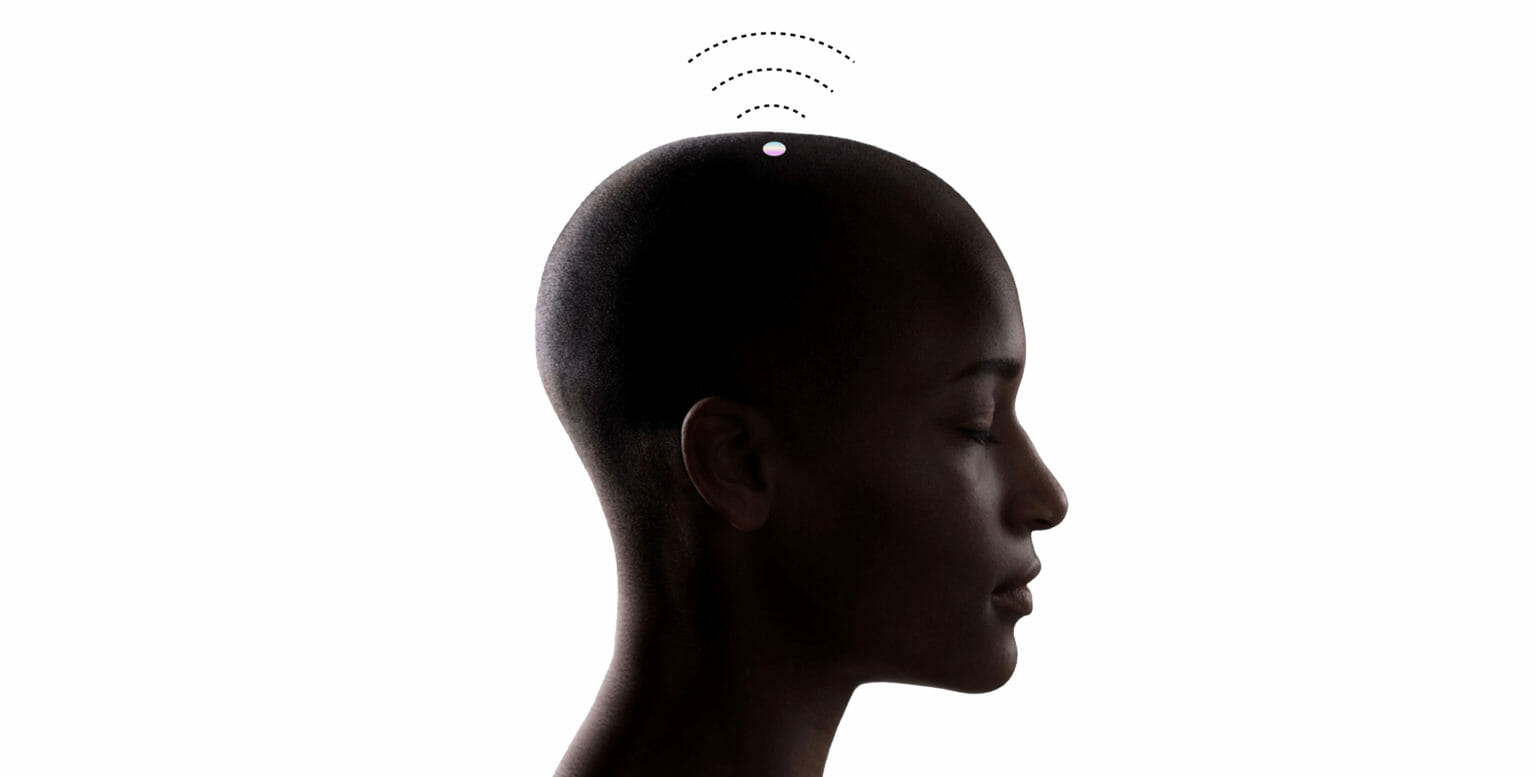

His vision is one of Lasik-like clinics where you can have a set of probes inserted into your cortex in a matter of minutes which has the ability to not only read what your neurons are doing, but can write to them as well–all through a wireless smartphone app.

Not surprisingly, early applications are focused on medical interventions, including the ability to counter the effects of neurological diseases like Parkinson’s disease, and restoring mobility to people with damaged spinal cords.

But what the folks at Neuralink really want to do is to create brain machine interfaces that massively enhance human performance–everything from gaming experiences where your brain is literally plugged into the console, to telepathy, and even symbiosis with artificial intelligence.

As with his other companies, Musk is on a mission to change the future on his own grounds–in this case, a future where who we are and even what we are is deeply influenced by the hardware that’s inserted in our brains, and the apps that control it.

Of course, the chances of many of the dreams of Neuralink’s developers coming true are pretty slim–at least in my lifetime. But in reaching for them, these entrepreneurs are warping the pathway between where we are now, and the future we’re heading for.

Because of this, it is absolutely critical that an understanding of the technology and its responsible and ethical development is built into our thinking around global futures. Otherwise, how will we navigate the shifting path between the present we inhabit, and the future we aspire to?

And in case you’re interested, here are my comments to the NASEM Committee on Science, technology and the Law:

Exploring the governance and ethics of Neuralink-like brain machine interface technologies

(Given to the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine Committee on Science, Technology and the Law, October 2, 2020)

I first wrote about the ethical and social challenges presented by brain machine interfaces in my 2018 book “Films from the Future.” Despite its somewhat misleading title, the book focuses on the complex challenges that potentially transformative trends in science and technology present us with, and how we as a society can better-understand how to navigate them responsibly.

At the time I was writing the book, Elon Musk’s company Neuralink was making waves, especially with its recruiting tagline of “No neuroscience experience is required.”

Two years on, it’s clear that Neuralink is adopting the same entrepreneurial model of technology innovation that’s led to disruptive and transformative change in other sectors in the past. And now that we’ve recently been given a glimpse into the company’s current work and aspirations, I’m more convinced than ever that it, and other enterprises working in this space, are raising ethical and governance challenges that we, as a society, are poorly equipped to navigate.

Of course, discussions around the ethical development and use of brain machine interfaces are not new. For decades now, there has been a close coupling between ethics and the development and use of device-based brain interventions for medical use, from cochlear implants to deep-brain stimulation, transcranial direct current and magnetic stimulation, and increasingly sophisticated sensor array like the Utah array.

And yet, my sense is that these discussions have been confined to a rather narrow lane that, while important, threatens to be marginalized by emerging developments.

Here, companies like Neuralink have attracted a certain degree of skepticism around their ability to push the limits of brain machine interfaces as far as they claim. It’s been pointed out by some that they are simply playing at the edges of what is already a well-established field. In some cases, I’m getting the impression from experts that they believe there’s nothing really new here, and that this also extends to the issue of ethical and responsible development.

Yet while I understand these responses, I believe that they’re misguided. The pivot point here is not necessarily new science or novel techniques (although I would argue that Neuralink and other companies are pushing boundaries here as well), but a synergistic scaling of ability, accessibility, and use, that has the potential to profoundly rewrite the landscape around how we use and think about brain machine interfaces.

At the heart of this is the way in which entrepreneurialism—especially a Silicon Valley flavor of entrepreneurialism—has the capacity to overtake the slow, careful development of new capabilities within the established medical community.

Entrepreneurs are driven to uncover how new and previously overlooked combinations of technologies, processes, and opportunities, can lead to profound—and hopefully for them profitable— shifts in what is possible. Not only do they not care for established ways of doing things, and the traditions and expectations of conventional disciplines; they actively seek to exploit these by finding opportunities that lie between the cracks of conventional thinking.

This is seen time and time again in how entrepreneurs exploit existing capabilities to create new opportunities, by taking chances and not following conventional wisdom. It’s a mindset that eschews how academics, lawyers and policy makers often think about the world, and even seeks to exploit this. And it’s an approach that disregards conventional knowledge, and actively looks to develop new capabilities by combining expertise in novel ways.

It’s this type of approach that has underpinned the success of companies like Tesla and SpaceX—sticking with an Elon Musk theme here—and is likely to lead to Neuralink confounding experts in what the company achieves and the ethical boundaries it pushes against.

Some of these ethical challenges are, of course, well-described in the literature, especially when it comes to machine-based interventions on medical grounds that may have unforeseen consequences to patients. These don’t worry me so much as we already have a handle on many of them.

What does worry me thought are the challenges that a blinkered perspective on medical neuroethics may lead to us missing—until it’s too late.

Watching the recent update on the latest developments at Neuralink, it’s telling that, when asked about their dreams and visions of a brain machine interface future, the company’s scientists and technologists were less interested in medical interventions, and more interested in how the technology can be used to enhance users’ abilities.

They spoke about enhanced cognitive abilities, memory storage and retrieval, gaming, telepathy, and even symbiosis with machines; all through an inexpensive, readily installed, massively-connected sensor array that’s wirelessly controlled from a smart phone, and that has the ability to not only read from the brain, but to also write to it.

Of course, the chances of many of these aspirations coming about is minimal—the brain is simply too complex and our understanding of how it works too limited to achieve what these developers dream of—at least for now. Yet this is not the point here. What’s important from a governance, ethics and responsible development perspective is that these entrepreneurs are in the process of reimagining what is possible. And while things will probably not end up where they hope, their work will nevertheless lead us into new and unexpected territory.

To get a sense of this, consider these five questions, which are just the tip of an ethics and governance iceberg I suspect:

- Who will be responsible for ensuring the ethical use of brain machine interfaces that are installed as an enhancement device, and that come with no explicit medical claims?

- How will widespread access to performance-enhancing brain machine interface technologies impact social norms and behaviors, and where do the ethical boundaries lie between what is acceptable, and what is not here?

- How do we ensure that users don’t become the victims of the technological equivalent of indentured servitude, where they need to pay for continuing technology and security updates or suffer the consequences?

- How might we approach the potential use of brain machine interface technologies that mimic or transcend the effects of illegal drugs?

- And finally, in this very incomplete list, how do we navigate a future landscape where apps can be used to alter the mind-state of brain machine interface users, without them having full autonomy over how the technology is affecting them—especially where the technology is integrated with machine learning?

Admittedly, some of these questions may lie beyond the realms of plausibility. But they do serve to highlight just how complex the ethical and governance landscape around brain machine interfaces is likely to become, if and when the technology becomes affordable, accessible, and focused on enhancing performance.

Navigating this landscape will require an equally dramatic shift in how we approach the ethics, governance and responsible development of the technology I believe, if we’re to see clear and substantial social benefits with manageable associated risks.

This is where our work on risk innovation at Arizona State University may be useful as part of a broader exploration of innovative approaches to responsible and ethical development.

The idea behind risk innovation is very simply using the concept of risk as a threat to value to help navigate an increasingly complex landscape between entrepreneurial dreams and aspirations, and their economically viable and socially responsible realization. It’s an idea that emerges from our work over the past several years on helping entrepreneurs make early decisions that support long-term ethical and responsible outcomes.

Our approach, and the tools we’ve developed, are built on protecting and growing current and future value that’s defined very broadly—and not just to the enterprise in question, but to their investors, consumers and the communities they touch. This includes social value and personal value as well as economic value—for instance, the value associated with equity, agency, and a sense of self.

Here, we focus specifically on what we call “orphan risks.” These are hard to quantify threats to value that often slip between the cracks of conventional risk approaches, and yet in today’s interconnected world can mean the difference between success and failure.

Last year, we published a paper that applied our approach to the technology being developed by Neuralink, where we mapped out key areas of value, and the corresponding orphan risks, that characterize the technology’s development. Looking back, I realize now that we were somewhat naïve in assuming that transformational medical interventions were a higher priority in the long-term for the company than enhancement technologies. But the exercise still provides a useful indication of how we as a society might need to start thinking more broadly about the ethical and governance landscape around emerging brain machine interface technologies.

From our analysis, a number of orphan risks stand out as requiring particular attention. These include perceptions around how the technology will be used, social justice and equity, loss of agency, organizational values and culture, and ethical development and use more broadly.

These and other orphan risks are not readily addressed within entrepreneurial enterprises, beyond what is required for medical applications. And more importantly, there are few frameworks currently in place that enable them to be addressed in agile and responsive ways.

Yet this will be critical if we are to see the benefits of a potentially transformative technology without ending up in an ethical quagmire.

The challenge here, of course, is that technologies like those being developed by Neuralink have the potential to rewrite the technology landscape before we realize what’s happening, and this is where new, agile approaches to technology governance and ethics are desperately needed. To underline this, I’d like to finish with an example that is not about brain machine interfaces, but is nevertheless relevant.

With his company Tesla, Elon Musk disrupted the car industry by bringing an outsider mindset to an established way of doing things. On the face of it, Tesla made electric vehicles trendy and desirable. But to think that Tesla is simply about electric cars is a serious mistake. Tesla is less about what we drive, than it’s about about how our surroundings, our actions, and our lives, are mapped and monetized, and how the fulcrum of converging technologies can be combined with the lever of imagination to fundamentally alter how we live.

Tesla is not a car company, but a tech company committed to changing our future on their terms.

Neuralink is setting out to do the same. Only in this case it’s our brains and our minds that provide the platform for their corporate future-building. And this raises ethical challenges that far transcend those that we’ve previously had to handle when considering brain machine interfaces.